The Victorian era gave us more than architectural silhouettes and velvet-draped interiors; it gave us a fascination with ritualized mystery. Nowhere is this more vividly seen than in the séance. To the modern imagination, séances conjure images of dimly lit parlours, flickering candles, hushed anticipation, and hands joined around a polished table. These evenings were not only about the possibility of contacting the dead. They were about mood, the ceremony, and inhabiting a liminal space between everyday life and something more shadowed, more suggestive.

Victorian séances were as much social events as they were spiritual ones. They were rarely horrific; instead, they blurred the lines between theatre, belief, and intimacy. They reveal how the Victorians transformed their parlours into stages, their homes into thresholds, and their everyday rituals into aesthetics that continue to inspire what we think of today as gothic coziness.

The Rise of Spiritualism

The modern spiritualist movement began in 1848, when the Fox sisters of Hydesville, New York, claimed to hear mysterious rapping sounds in their family home. These “spirit rappings” quickly gained popularity as a cultural phenomenon, and within a decade, spiritualism had crossed the Atlantic and become deeply entrenched in British society.

For Victorians navigating a rapidly changing world—science challenging traditional faith, industry altering landscapes, mortality pressing in through disease and war—spiritualism offered both comfort and spectacle. It promised continuity with the departed, but also provided a thrilling new form of entertainment. One could sit in a respectable drawing room and, through candlelight and ceremony, touch something unseen.

The Parlour as a Stage

Séances were usually held not in public halls but in domestic parlours, the most refined and social space of the Victorian home. These rooms were already designed for drama: heavy curtains, ornate wallpaper, dark woods, oil lamps, mirrors, and patterned rugs. By drawing the curtains and lowering the lamps, the ordinary parlour became something extraordinary—a threshold.

The séance began with ritual. Guests were arranged around a table, hands lightly touching. Silence fell. A prayer or invocation might be spoken. A central candle might be lit. These gestures, while simple, created a shift in perception. As one participant described:

“The silence was unbroken, save the faint ticking of a clock. Each of us sat with hands joined, waiting. The shadows grew deeper until the parlor seemed no longer our own, but a place suspended.”

— William Michael Rossetti, séance diary, 1866

The room was not just decorated; it was curated for aesthetic. Expectation itself became part of the ritual.

Phenomena and Suggestion

What followed in these gatherings was rarely dramatic in the horror-film sense. The power lay in subtlety.

- Raps and knocks: Gentle tapping sounds—on walls, under tables—were the most common manifestations. A code of knocks often stood in for yes/no answers from the spirits.

- Table movements: The table might tilt, sway, or rise slightly. The effect was gradual, more uncanny than terrifying.

- Spirit voices: Mediums sometimes spoke in altered voices, claiming to channel the spirits of departed loved ones.

- Automatic writing and slate messages: Hands guided pens to scrawl notes, or chalk slates beneath the table revealed brief spirit communications.

- Touches and breezes: Some reported faint touches on the hand, a brush of fabric, or a sudden coolness in the room.

Theatrical mediums sometimes offered more ambitious spectacles: phantom hands, floating instruments, or even “ectoplasm.” But most séances thrived on suggestion, not spectacle. A flicker of movement in the half-light, the shuffle of a curtain, the faint creak of a chair—these were enough to stir imagination.

One American diarist, John A. Clark, attending a séance in Santa Fe in the 1860s, noted:

“The faintest creak set all our nerves on edge. It was not fear, but expectancy, sharpened by the stillness of the parlor. The table shifted slightly beneath our hands, and though no voice was heard, it was enough to convince half the party that we had touched the veil.”

These accounts suggest that the séance was as much about perception as it was about phenomena. The aesthetic was the experience.

Mediums and Performance

At the center of the séance was the medium. Some became celebrities—Daniel Dunglas Home, renowned for levitations and phantom hands; Eusapia Palladino, famed for dramatic table movements; Henry Slade, notorious for his slate writings. They moved in fashionable circles, invited into aristocratic homes, their abilities both celebrated and scrutinized.

Mediums blended charisma with performance. Many of the participants were women, and in a society that denied them political authority, the séance gave them a paradoxical kind of power. As historian Alex Owen observed, the medium’s trance state allowed women to speak with authority, even to challenge male skepticism, under the guise of spirit possession. In the dim light of the parlour, boundaries of gender and power shifted, if only temporarily.

Theatricality was undeniable. Curtains, cabinets, and dim lamps created spaces where sleight of hand could flourish. Fraud was frequently exposed, yet the mood lingered nonetheless. As one skeptical observer admitted after catching a medium freeing her hand from the circle:

“Though the trick was laid bare, the aesthetic had already enchanted us. We were willing, for an hour, to believe.”

This is what made séances compelling: belief and doubt existed side by side, held in the same candlelit air.

Memory and Keepsakes

For Victorians, séances were not only about mystery—they were about memory. The 19th century was an age obsessed with remembrance: hair lockets, pressed flowers, portrait photography. Séances fit this culture perfectly.

Messages from loved ones, however faint or ambiguous, could be cherished. Automatic writings were folded into letters, slate scribbles preserved as relics. The séance turned absence into presence, echoing the way a photograph made a loved one’s face linger beyond death.

This aestheticization of memory resonates with our own digital practices today. Just as Victorians pressed flowers into books, we pin images to boards. Just as they framed portraits of the departed, we curate feeds of aesthetic moments. Both are ways of making the fleeting endure, of turning feeling into artifact.

The Skeptics and the Believers

Not everyone was convinced. Scientists, magicians, and commissions investigated mediums, exposing many as practitioners of trickery, including the use of false limbs, hidden wires, and sleight of hand. Figures like Harry Houdini made it a personal mission to expose fraud. Yet even repeated exposure didn’t entirely dim the allure.

Why? Because the séance was not just about proof. It was about ritual, mood, and longing. The experience mattered, even if the “evidence” was questionable.

As Rossetti wrote after a particularly ambiguous séance:

“I left with no certainty of spirits, but with the sense that I had dwelt, for a little while, in a chamber touched by mystery. That in itself was worth the hour.”

The Enduring Legacy

Today, when we picture gothic coziness—candlelit rooms, velvet shadows, whispered mysteries—we are drawing directly from the imagery of the Victorian séance. These gatherings were not about blood or terror, but about aesthetics: dim light, suggestion, and the invitation to wonder.

They remind us that mystery can be beautiful, that shadows can be comforting, and that ritual itself can be an art. The Victorians may have gathered in hopes of touching the unseen, but what they truly created was an enduring aesthetic—a parlour of spirits, where elegance and aesthetic mattered as much as belief.

And so we continue their legacy. Each time we light a candle against autumn dusk, or curate a mood board of cozy shadows, we are echoing those evenings in Victorian parlours—where the mood itself was the experience.

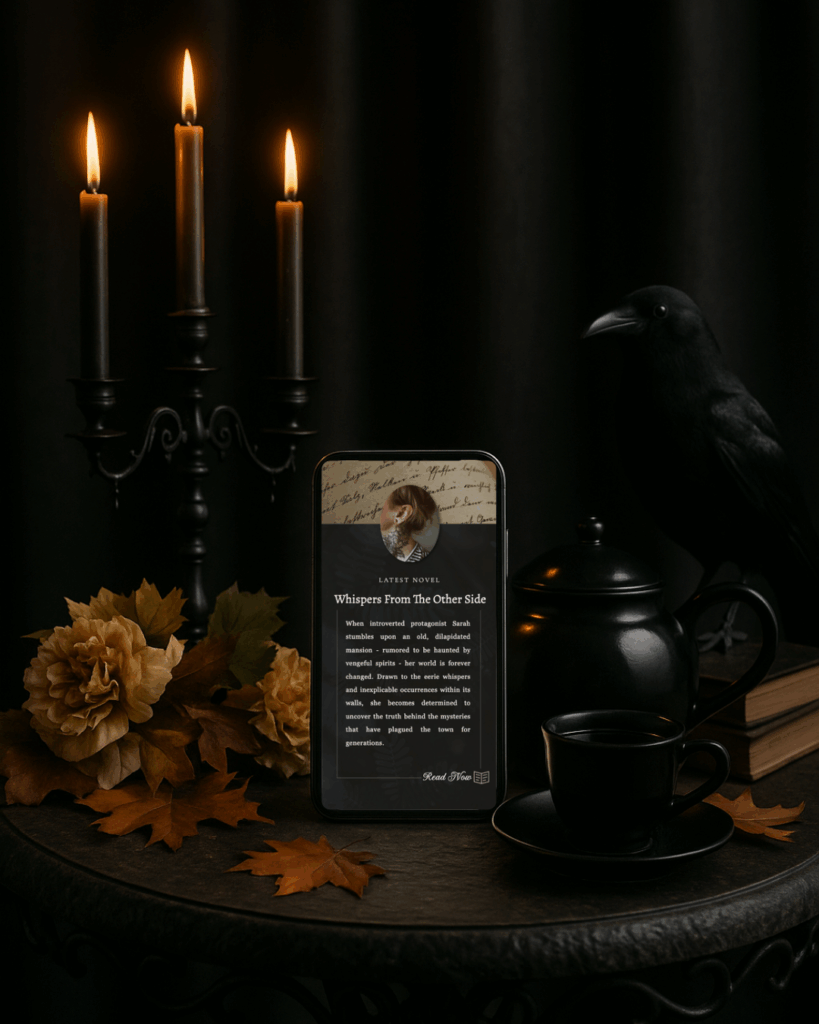

Create Your Own Victorian-Inspired Aesthetic

If the Victorian love of ritual resonates with you, why not incorporate that same sense of ceremony into your online presence? At A Season of Stories, I design gothic and bookish website templates, Instagram packs, and digital bundles inspired by folklore, parlour coziness, and Victorian detail.

Explore this Victorian Website Template Collection or discover these Dark Academia Instagram Templates to craft a digital home as atmospheric as your favourite novel.