Summary: Online culture is saturated with eerie visuals, yet this isn’t new—it echoes centuries-old fascinations with the strange and the haunted.

You scroll past it without noticing at first—a photo of an abandoned hallway, peeling wallpaper curling like parchment, a single flickering light in the background. It’s artfully blurred. The caption reads nothing more than a quote from Poe or maybe an old folk saying, something ominous and poetic. It has thousands of likes.

This is the haunted feed.

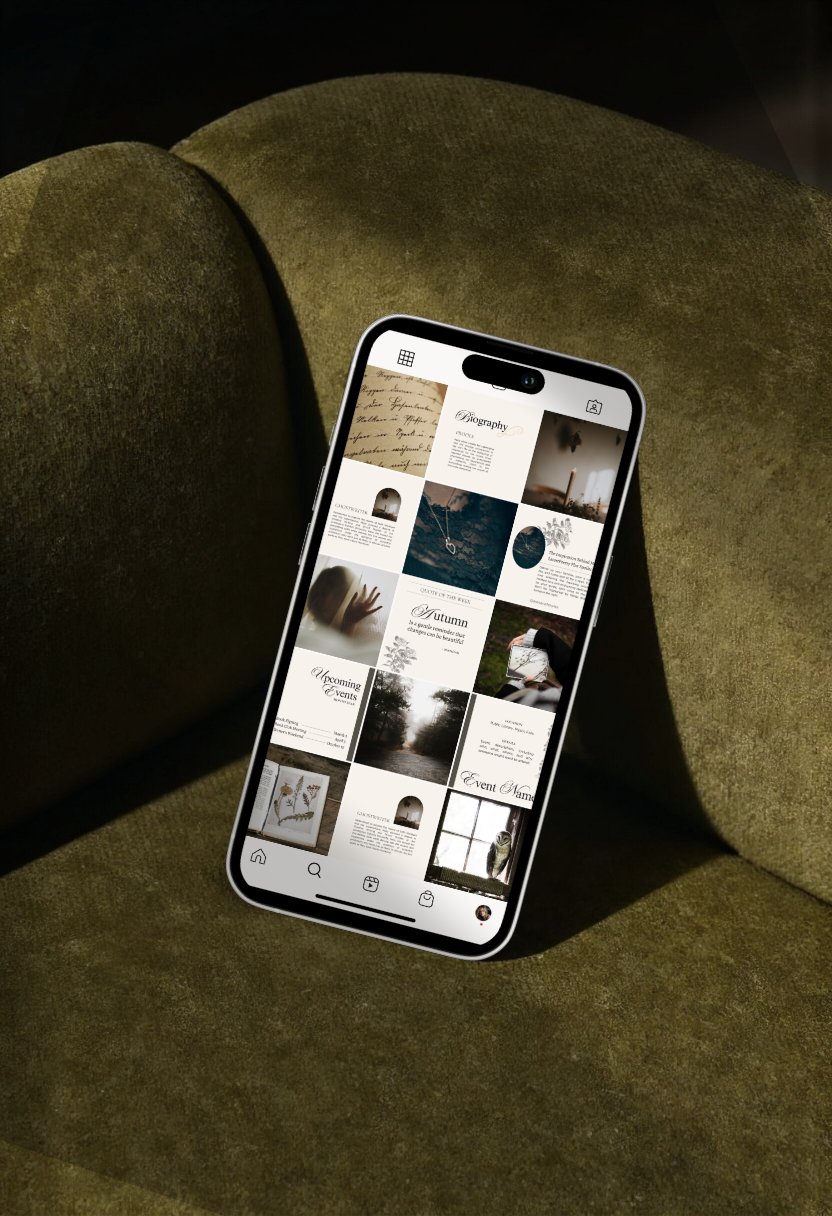

The internet today is haunted in every way except literally. On platforms built for bright, marketable identities, an entire countercurrent pulses with shadows: dim candlelight, broken windows, soft-focus cemeteries, moss-covered stone, Victorian locks, and decaying dolls. These visuals recur again and again, embedded in aesthetic subcultures, recycled as visual metaphors, shared with captions about nostalgia or poetry. You see it in curated Instagram grids, in “dark academia” TikToks set to classical piano, in gothic Pinterest mood boards, and in AI-generated art that blurs ruins with angels and skulls.

It feels new because it is digitally native—but it isn’t new at all.

To understand the rise of this phenomenon, we have to look not just at platforms but at the aesthetic desires that have remained constant for centuries. The internet didn’t invent the haunted—it digitized it. It made ghosts shareable. It turned nostalgia into an algorithm-friendly emotion.

The Old Roots in a New Medium

The gothic aesthetic—visual and emotional—is one of the longest-surviving cultural expressions in Western art. It began with architecture, took root in literature, and found modern echoes in film and fashion. Its key components—decay, shadow, grandeur, mystery, the unknown—persist because they engage a set of universal human anxieties: What happens when things fall apart? What lingers after? What cannot be explained?

The rise of the haunted feed is simply this logic adapted to digital form. Our platforms, especially those based on images, have become curators of mood. And the haunted aesthetic—strange as it may seem for an era obsessed with productivity and branding—has become one of the dominant moods of the digital self.

There’s irony in this. Social media was meant to be bright, clean, and efficient. Yet many of its users seek out a visual language of slowness, gloom, and weight. They want cracked windows, not ring lights. They want ancient scripts, not sans serif. And they don’t just want beauty—they want beauty with the depth of history in it.

That tension explains the haunting. It’s not merely about ghosts or the supernatural. It’s about aesthetics. The haunted aesthetic online is a visual rebellion against the sterility of digital spaces. It says: I refuse your clean lines. I want dust, rust, and to feel the passage of time.

Aesthetics as Emotional Language

Digital culture privileges clarity, simplicity, and speed. However, Gothic aesthetics reject all of those. They are maximalist. They are emotionally ambiguous. They take time to absorb.

This is one reason the haunted aesthetic resonates so profoundly with younger digital users, especially those born into the overexposed transparency of social media. If everything is visible, everything also becomes performative. Haunted aesthetics allow for a retreat—into shadow, mystery, half-truths. They feel honest in their opacity.

A picture of a mossy grave might not tell a clear story, but it suggests a thousand stories. It is a space of narrative potential. That’s what draws people in. In a world demanding constant clarity, the haunted offers ambiguity. It gives permission to feel sad, confused, strange, or out of place.

The Gothic as an Online Identity

More than just mood, haunted aesthetics have become a form of identity signalling. When you post photos of ruined castles or foggy woods, you are saying something about who you are—not just in taste, but in temperament. You are affiliated with a subcultural lineage that values introspection, history, melancholy, and mystery.

This is where the gothic separates from mere darkness. The haunted feed isn’t just about horror. It’s not jump scares and blood and gore. It’s about emotional resonance. There is nostalgia in it. There is longing.

Sometimes this takes form in gothic fashion: corsets, lace, veils, and heavy boots styled for the camera. Other times it’s literary: quoting Byron, Poe, or Dickinson alongside moody portraits. However, it is always a way of narrating selfhood through symbolism.

The haunted aesthetic is compelling for those who feel dislocated from modern norms—such as gender expectations, capitalist productivity, or cultural pressures. It allows space for resistance, slowness, and emotion. That’s why it thrives among quiet creators, neurodivergent communities, and artistic subcultures.

The Algorithm Loves the Gothic

And yet: the irony deepens. Platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Pinterest reward haunted aesthetics precisely because they perform well. Dark visuals stand out in bright feeds. Melancholy quotes get shared more often than cheerful ones. Lo-fi horror videos rack up millions of views. The haunting has become viral.

In this way, the feed becomes haunted not just in mood but in structure. The same motifs—cobwebs, stone arches, fog, old portraits—recur because they work. They engage. The user is drawn in, again and again, to the aesthetic of darkness, which has become one of the most lucrative online aesthetics.

So now, creators find themselves in a strange loop: posting ruins to build a following, quoting the dead to grow a brand, and adopting Gothic visuals to express authenticity. The haunted feed is real, but it is also curated. It is emotionally raw, but it is also strategically framed.

Still, there is something real in it. Amid the performance, the filters, the branding, something of the original gothic impulse survives: the longing to see what lies beneath the surface, to remember the past, to feel what has been forgotten.